The most radical changes in American universities

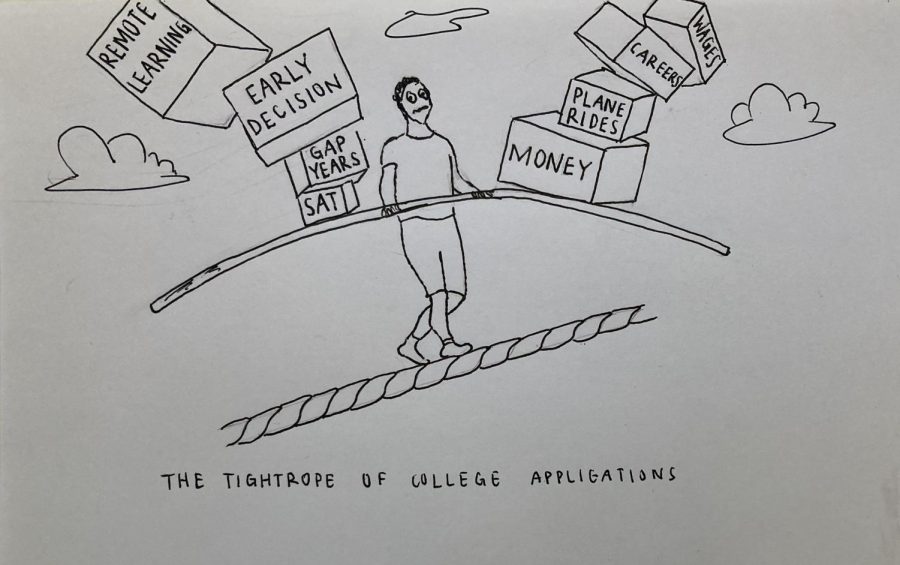

Original cartoon by Alisha Bhatia

Senior Alisha Bhatia examines the decline of early applicants in American universities

November 3, 2020

On June 18th, Emily Oyster published a simple Google form survey to her blog and it would soon become one of the best sources on the coronavirus in schools. But this is not something to be excited about. While the Brown University economist definitely earns the praise, it is “a horrible, embarrassing disaster” that her relatively small reaching survey became a data source better than the government’s or data companies’, according to Oyster herself[1]. In the face of this uncertainty regarding schools and colleges during the pandemic, here’s what we know:

- Less students are applying Early Decision. The application plan allows students to apply to their top choice school early (typically by the start of November), and given that they are accepted, includes a binding agreement of attendance. What’s the benefit for students? Applications submitted during this time have higher acceptance rates, and especially in elite universities like Harvard with acceptance rates lower than 5%, every advantage helps. However, this application plan requires that a student be sure on their top choice school – there’s no backing out.

During this application season as things are still uncertain but unlikely to return to “normal” by next fall, trends show that fewer students are applying early. Does this mean that those who apply early will have an even larger chance of acceptance than normal? No one knows for sure, but one thing remains true: in such a time of financial, medical, and academic instability, students report that guarantees just can’t be afforded.

The fact that more classes will be conducted online and in a dorm room or apartment also contributes to this decline in early applications, and leads us to our next point:

- Students are staying closer to home. Plane rides have now transformed from small annoyances and catalysts for cramps to barriers to health and the ability to visit home for some. Accordingly, state schools are reporting a greater number of expected applications – students are choosing to attend schools just a car ride away. However, this also means that local and state universities may have to be more selective in these next few years.

- SAT and ACT exams are becoming less important – and not just for the incoming class. The pandemic hit just before the month when the bulk of high school juniors take their first SAT exam – March. As a result, nearly all colleges have decided to go test optional, test blind, or test flexible, meaning that students can choose not to include these exams in their applications without having to worry about it negatively affecting their acceptance chances. Some colleges have even gone beyond the high school class of 2021 and preemptively stated that test scores will not be required for the next 4 classes. This may be temporary, but the sudden shift to a widespread test optional or test blind policy may be the perfect time to deemphasize standardized test scores.

- More students are taking gap years. In hopes of returning to school under more typical circumstances, reports show more students taking gap years. The trick is to find something productive to do during this gap between formal education – an even more difficult task now that many internships and similar activities have been cancelled. This struggle may only be temporary though, because employers are quickly adapting to these changes and offering more remote positions.

- The postgraduate workforce may look entirely different. As companies like Microsoft are converting some positions to be fully online, positions that high school students may seek after their college education is completed may not be in offices with workers. So long are the days of water cooler talk and long commute times – Mark Zuckerberg announced that almost half of its employees may remain online for five to ten years, and Twitter employees may work online indefinitely if they choose. As employers find that office spaces and similar accommodations can now be optional expenses, they might just choose to avoid this cost.

[1] https://www.npr.org/transcripts/924583724